How to measure heat: temperature versus heat flux

Heat, heat flux and temperature are all related, but refer to different quantities in thermodynamics. Why does a surface feel hot? Am I feeling a temperature difference, or do I feel transfer of heat? It is clearly important to know the differences between these concepts. Understanding heat-related measurement, and its dynamics is important for optimising various processes in science and industry. Heat, heat flux and temperature: in this article, you will find the differences, similarities and how they are related.

Heat and temperature explained

Heat is energy, thermal energy. Heat can be transferred between systems or objects with a temperature difference. The transfer of energy continues until thermal equilibrium is reached, meaning both systems or objects have the same temperature. Because heat is a form of energy, it does not have a direction; it is a scalar quantity measured in Joules or kilowatts. But the transport of heat does have a direction making it a vector quantity. This will be further elaborated below.

Temperature refers to the amount of kinetic energy of vibrating and colliding atoms within that object. Thus, if more heat is stored in an object, the higher its temperature, making temperature of an object a measure of heat stored in it. Temperature is often measured in Celsius (°C), Fahrenheit (°F) or Kelvin (K). The scalar quantity Kelvin (K) is used in the International System of Units (SI), therefore you will see Kelvin in most scientific articles.

Heat transport: flux and heat flux?

To understand heat flux, we start by giving its definition.

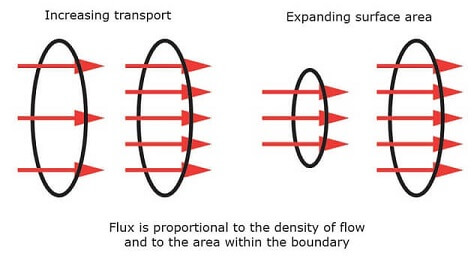

Flux is the passing or travelling of an effect through a certain surface in a given time period. It is expressed in Watts [W]. Flux can be increased by either expanding the surface area or increasing the transport through it per unit of surface area. Flux may be in the form of electricity, magnetism, or heat. The transport of heat through a certain surface area in a given time period is called heat flux.

Heat flux is measured in Watts per square meter [W/m2]. It is a vector quantity because it has a magnitude and direction.

Importance of heat flux measurements

Accurate measurements of heat flux are valuable for gaining more information about the efficiency of insulating materials and highlighting areas vulnerable to energy loss. When you use high-quality calibrated sensors, you ensure that you will get more accurate measurements. Such accuracy is important during research and development, providing insights that may lead to improvements. For example, this could result in better development of energy-efficient solutions in sustainable energy practices, design of buildings, machinery, etc. Therefore, committing to accurate heat flux sensors and measurement techniques helps find sustainable solutions for the future.

Accurate measurements of heat flux are valuable for gaining more information about the efficiency of insulating materials and highlighting areas vulnerable to energy loss. When you use high-quality calibrated sensors, you ensure that you will get more accurate measurements. Such accuracy is important during research and development, providing insights that may lead to improvements. For example, this could result in better development of energy-efficient solutions in sustainable energy practices, design of buildings, machinery, etc. Therefore, committing to accurate heat flux sensors and measurement techniques helps find sustainable solutions for the future.

Measuring heat flux, heat, and temperature

The first step in measuring heat flux is identifying the type of heat transport you are dealing with. There are three mechanisms to transport heat:

- Conduction

- Convection

- Radiation

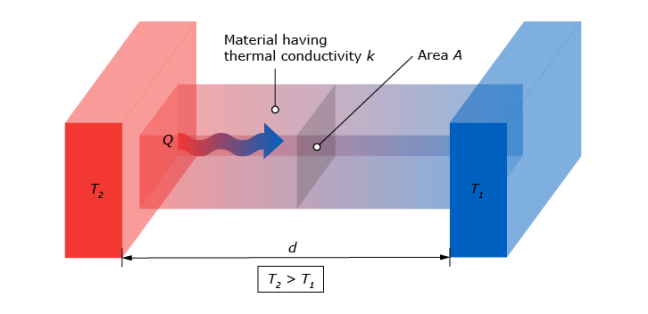

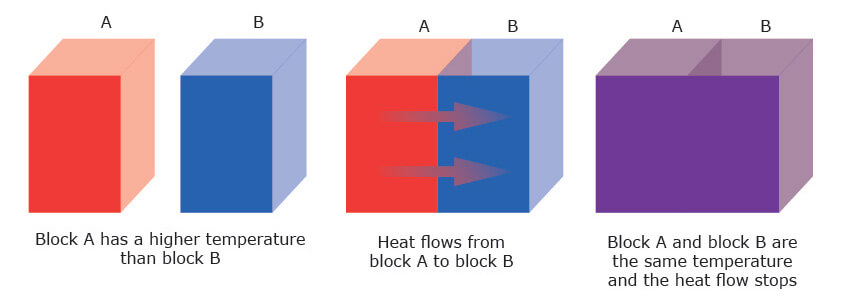

In heat flux by conduction, heat transfers from the hotter to the colder end of a body as in Figure 2. In conduction, heat transport is driven by a temperature gradient. Heat flows from a region of higher temperature to one of lower temperature. This heat transport will continue until thermal equilibrium is reached where both bodies have reached the same temperature.

having contact, one object hot and one cold, followed by thermal equilibrium.

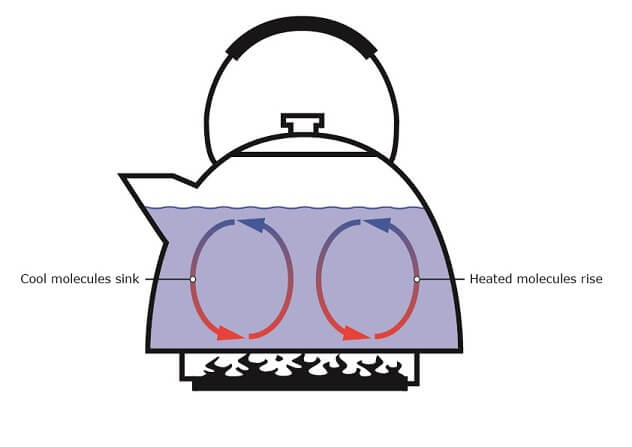

Heat flux by convection is the transfer of heat from a certain point in space to another by a flowing fluid or gas. Figure 3 illustrates a kettle with water being heated. Convection causes the water at the bottom to expand and become less dense as it expands. These heated water molecules will then rise, and the cooler molecules will sink to the bottom of the kettle. Subsequently, the cooler water molecules get heated and rise again. This cycle is repeated until all the water is the same temperature and starts boiling. This process is called “thermal convection”.

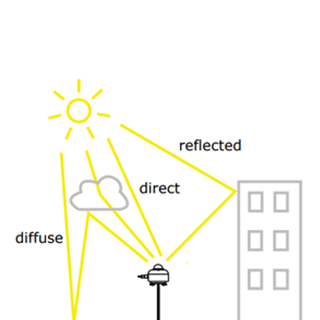

Heat flux by radiation, in contrast to conduction and convection, doesn’t need a medium - gas, liquid or solid - for transport. Radiation is exchanged between two bodies as shown in Figure 4. Here, the two bodies are separated by a transparent medium, i.e., transparent to thermal radiation. The fireplace radiates largely invisible infra-red heat through air to your cold hands, which absorb it. At the surface of your hands radiation is converted to heat.

Radiation can also occur from a blackbody. A blackbody is a diffuse emitter, meaning it emits radiation uniformly in all directions. It also absorbs all incident radiation, regardless of wavelength and direction, as shown in Figure 4 on the right. Many objects in daily life act as “blackbody radiators”. Only when they have high temperatures you will notice they emit radiation.

Hukseflux also provides heat flux sensors with black and gold stickers to separately measure convective and/or radiative heat flux.

A well-known source of radiative energy is the Sun. Read a more detailed explanation for solar radiation measurement. The combination of heat flux generated by these 3 mechanisms is the total heat flux.

On the right, radiation being emitted from a blackbody.

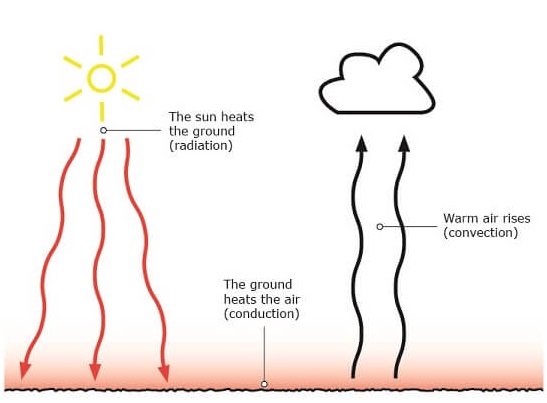

For example, Figure 5 visualises the earth’s surface and the atmosphere. Here, all three types of heat flux are present. The sun radiates heat through the air on to earth’s surface. The heated ground then heats the air through conduction. Simultaneously, the heated air from conduction rises and later cools down, transferring heat through convection.

In short, heat flux is the measure of how much heat is transferred through a certain surface area in a given time. Temperature, on the other hand, is the driving force for heat exchange, as well as an indicator of how much heat is present in a system.

Accurate measurement tools for the three types of heat flux are crucial for facilitating the development of energy-efficient solutions.

Hukseflux provides heat flux sensors for all types of heat transfer conduction, convection, and radiation. For a more detailed explanation to measure heat flux, please read: How to measure heat flux.

The table below gives an overview, presenting the features and characteristics for heat, heat transport, heat flux, heat capacity and temperature.

| Heat | Heat transport | Heat Flux | Heat capacity | Temperature | |

| Definition | Thermal energy | Transfer between hot and cold systems. | Rate at which heat is passing through a certain surface. | Defines how much heat is required to raise the temperature of an object by one degree Celsius. | Driving force for heat flux Defines the amount of kinetic energy of vibrating atoms inside a substance. Expressing when an object is hot or cold. |

| Property | Proportional to temperature and heat capacity of object. Heat moves from hot to cooler environments. | Faster transport proportional to temperature difference. | Amount of heat that moves from hot to cooler environments through a certain surface. | Depending on the object and its amount a specific heat capacity is given. | Temperature increases when an object is heated and decreases when cooled. |

| Units | Joules (J) Calories (cal) Kilowatt (kW) | / | Watts per square meter (W/m2). | Joules per kelvin (J/K) | Kelvin (K) Celsius (°C) Fahrenheit (°F)

|

| Device | Calorimeter | / | Heat flux sensor | Calorimeter | Thermometer |

| Symbol | Q | / | φ | C | T |